Add credibility to your idea in 8 easy steps

The word “research” connotes images of bowties, books and boredom. Laborious journeys through volumes of life’s works recorded in inaccessibly obtuse collections of words. As most often the overeducated person in any room, I speak from experience. For me, the hardest part of writing a Doctorate Thesis was not the writing, but rather figuring out a system for how to research and how to write. Turns out I am not alone — according to research reported in The Science Teacher Journal, most students report topic selection, followed by study construction and time management as the biggest challenges in conducting research.

Research process dogma

According to just about every Academic:

Good research is a well defined process where one reads a lot of credible literature, identifies the gaps that exist in the current credible literature, and from that, one articulates a unique research problem.

Snooze. Panic. Google Scholar Overwhelm. Snooze again.

Having spent years flitting in and out of Academic settings, I have found my own way of conducting research that is effective, fast, and for people wired like me, a lot of fun 🎉 Here are my 8 easy steps to turn any idea (research topic) into a credible piece of work (blog post, academic paper, book chapter, email to your Mother).

Don’t start with a blank page

Blank pages are scary. Starting a research project bottom up, i.e. by reading every piece of writing related to your topic area is unfeasible. According to Google Scholar, there are around 1.72 million academic papers on household waste — about 104,000 of these were written in the last 5 years alone. No one has enough time to read all these, not even the speed readers amongst us.

Instead of staring at your blank page, and suffering from the first and biggest obstacle to doing research (topic selection), go for a walk. Clear your head and brainstorm some ideas. Inflatable leggings for safe bungee jumping, flat-packable vertical gardens for domestic lettuce farming, an app to swap leftovers with neighbours, ways to reduce household waste. Dream big. Create the largest, most expansive idea space that you can. Remove all limitations to your thinking, and simply explore things that you have a natural interest in.

When you finish your walk, sit down and write down all your ideas on piece of paper. Now that your paper is no longer blank, you are ready to start your research.

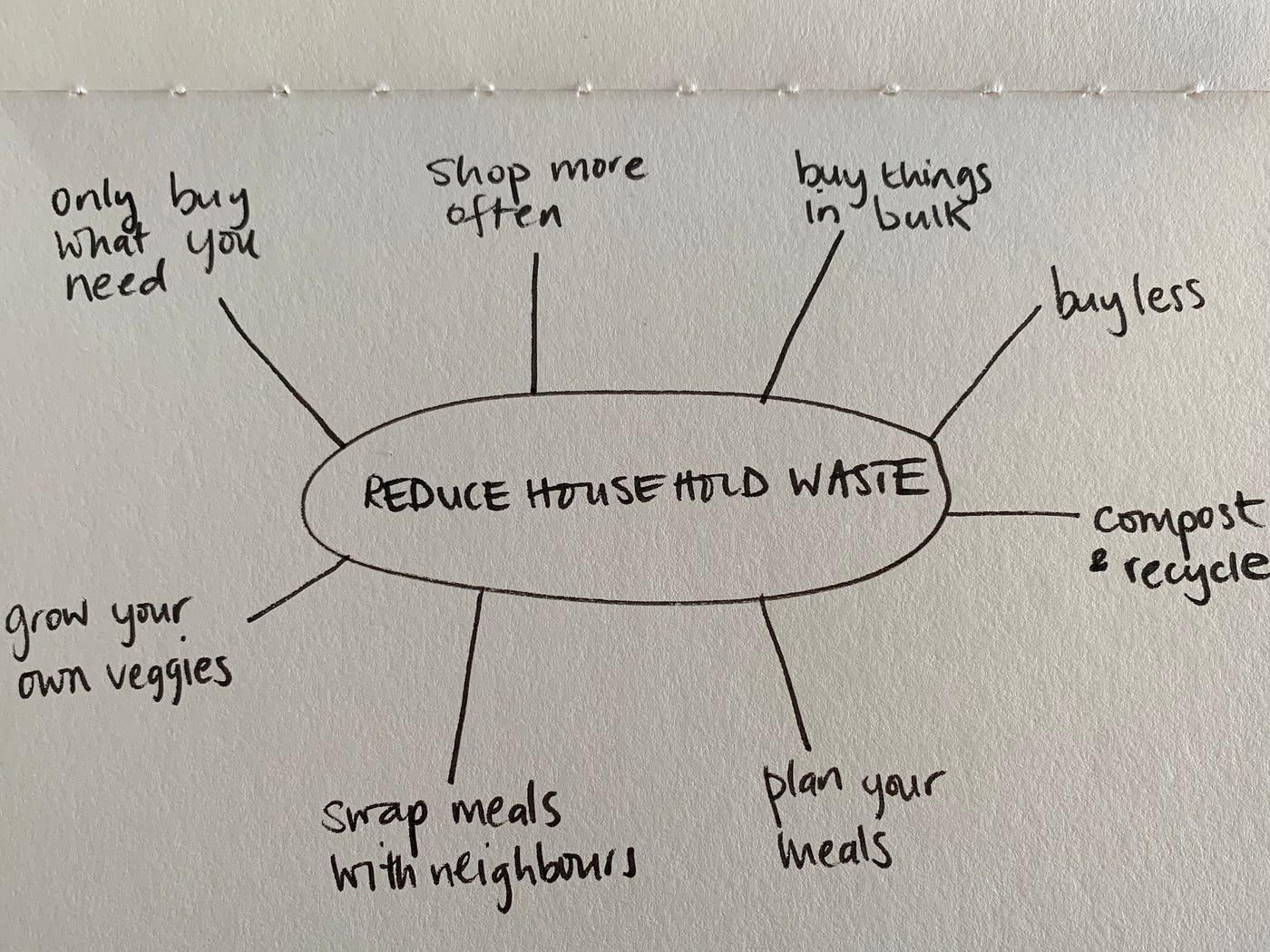

Step #1: sketch out an expansive idea space that aligns with your natural interests

My idea space around reducing household waste

Identify core issues

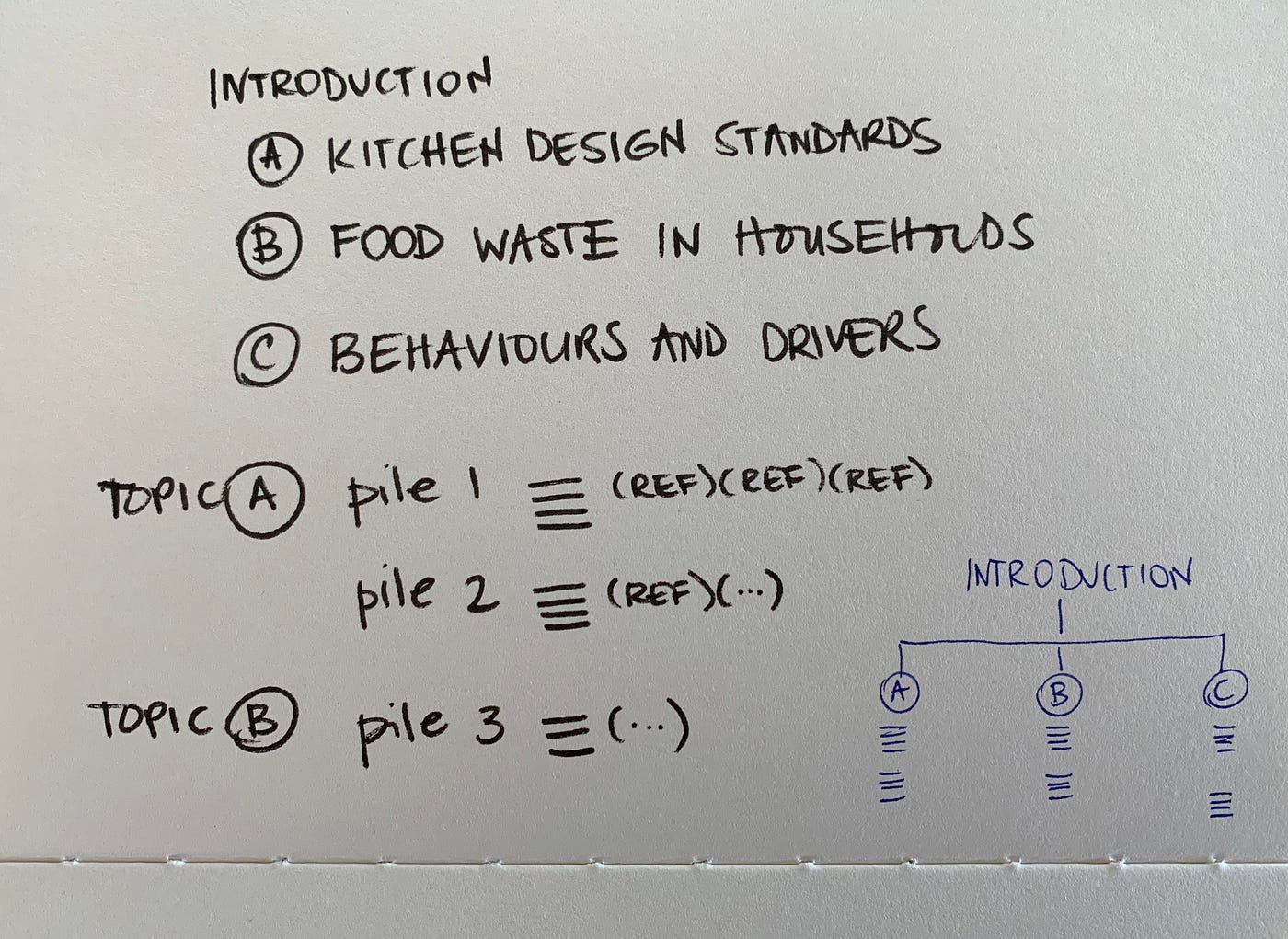

Next, take your idea space and break it down into core issues. Core issues are a set of themes, or topics (or keywords) that are relevant to the idea space that you are interested in investigating.

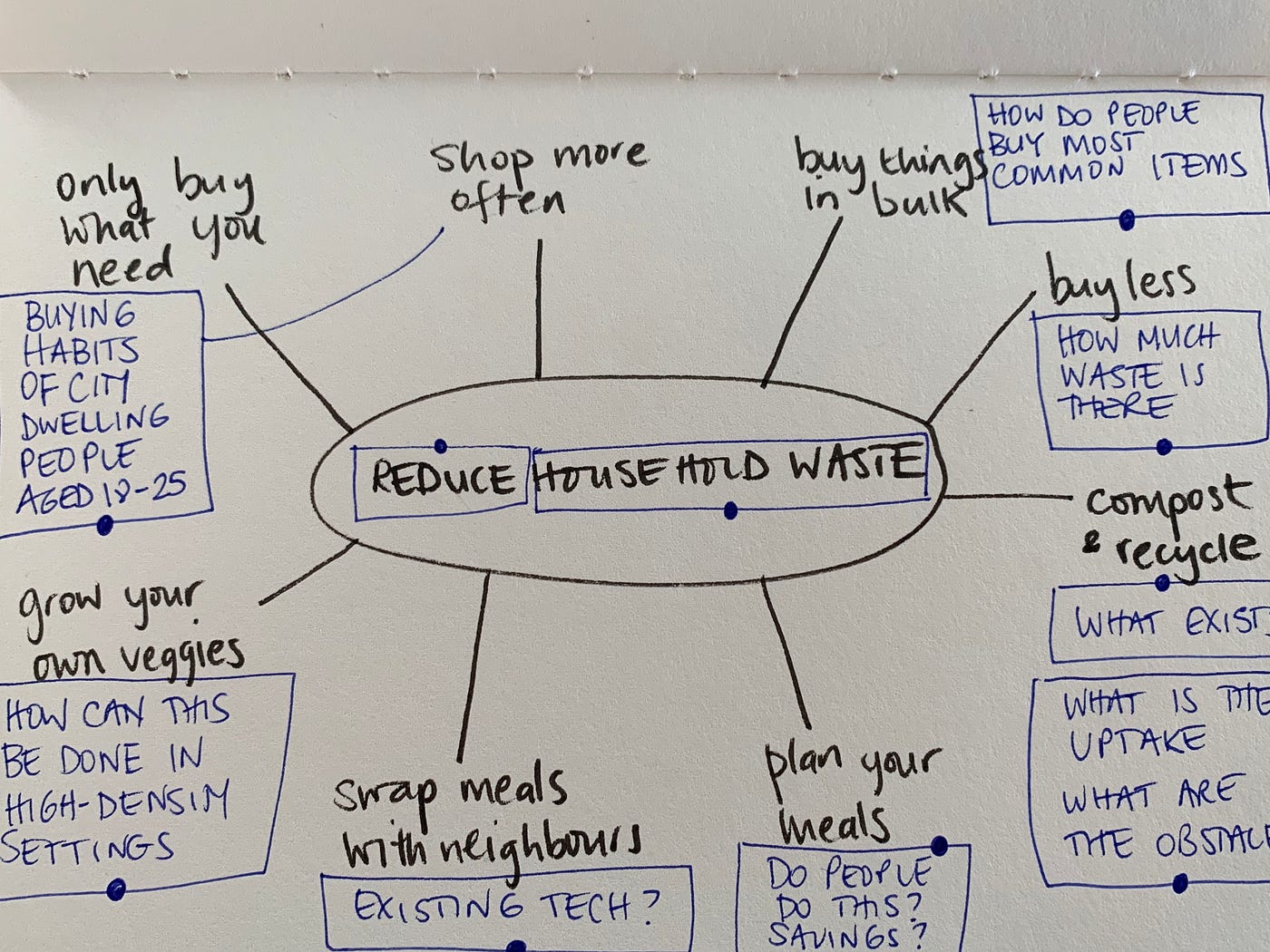

In the above example, I would take the idea space, and start to add notes that relate to the core issues: e.g. to figure out how to reduce household waste, I would need to understand what people currently buy, in what quantities, and how much of this results in waste (both unconsumed items, and also waste from packaging). Keep breaking the core topics all the way down to first principles — that is, basic assumptions that cannot be broken down or deduced any further.

Core issues related to my idea space

When you are finished this process, you will have a list of themes, or keywords that you can start to interrogate on Google Scholar. In the above example, I would start by searching for sources of household waste, and examining the first three results.

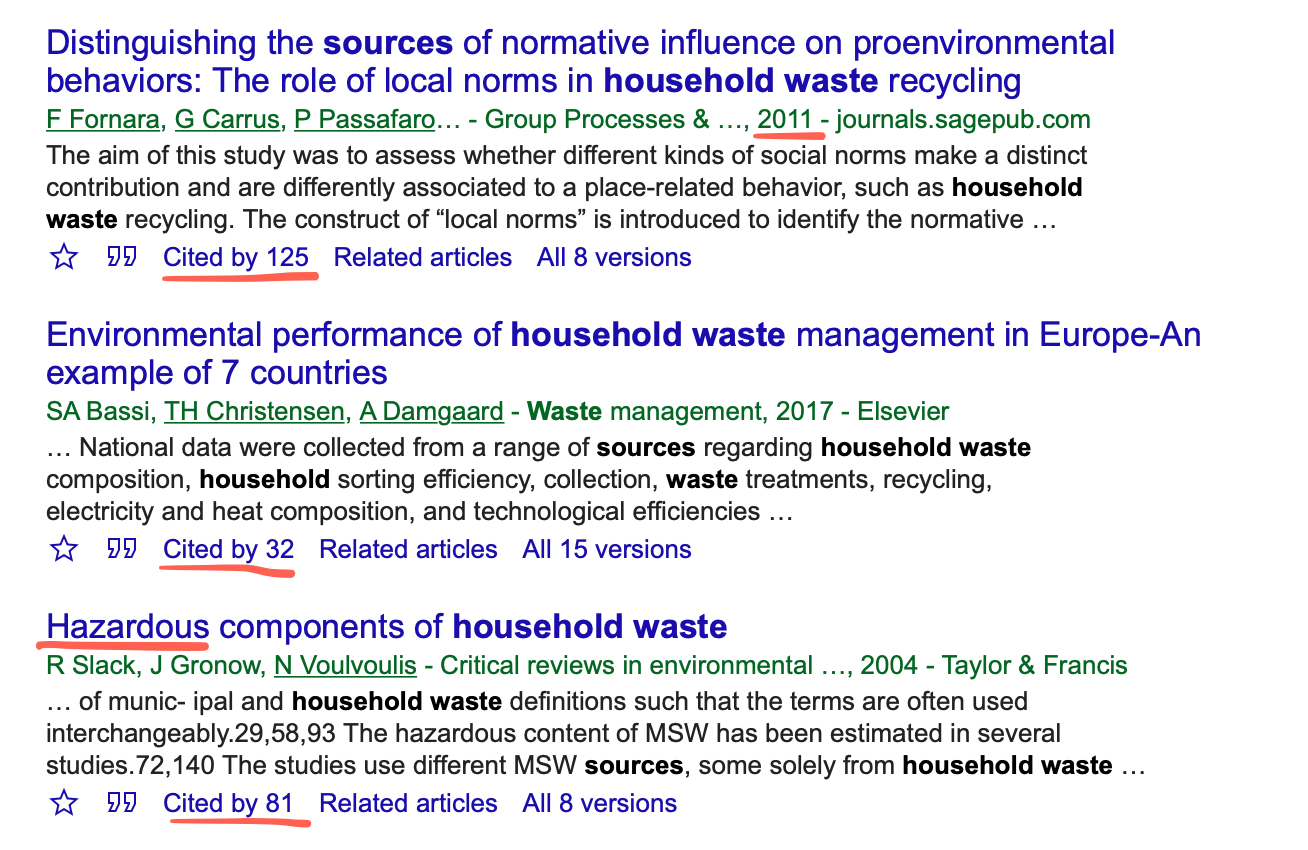

Search results from Google Scholar for sources of household waste

There are still close to a million academic papers related to sources of household waste, but the search space is much more narrow. I get a sense of this by looking at the first few results from Google Scholar — recent papers, all from academic journals with a decent amount of citations (this is a count of how many other authors have referenced a particular work), all reasonably on topic (I get this from the paper titles). If the first few search results look broad (e.g. household waste returns papers about the economics, management at a city level, composition, and recycling), it’s usually a clue that your core issues can be broken down a little further.

Repeat the process for all your core issues, saving links to one or two well cited papers related to your theme. Once you have your links, print (or whatever method works for you) these papers, and read the abstract + introduction of each paper only. Write down a summary sentence (about the paper) at the top of each paper. You will now have a broad sense of what researchers find inetersting and are investigating in your idea space.

Step #2: break your idea space into core issues and first principles, and read only the abstract + intros of key papers

Reality check and validate that “someone cares”

Most academic research takes around 20 years to go from academic paper to commercial adoption. Sometimes it takes longer — liquid soap was invented in 1865, yet it did not become a household item until 1980, when the pump dispenser was invented and mass produced.

The ideation space you created, and the core research areas that you identified, will have resulted in a wide range of topics. Having a broad sense of the kinds of research that exist in the space, the next really useful step is to road test what is “most cared about”. To do this, you will need to poll a few people.

In the household waste example, I would construct a two question survey and float it out to a group of people that repreesent my target audience. As I am interested in reducing household waste in urban dwelling citizens aged 18–25, I would seek out a few people who match this demographic using whatever means I can — over coffee, on Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, Discord, Slack, Email, Phone… and ask these people two questions (1) are you interested in household waste reduction (your topic) and (2) why? The answers above give you two very important datapoints.

Firstly, from question one you will have a sense as to whether anyone cares about your idea space. It may be that no one cares about your topic. If this is true, you have a couple of choices: rethink your topic, or, if your passions are strong enough, choose to continue with awareness that you are working on something either very niche or very groundbreaking.

The second question, why? (ask Simon 😂) will give you insights into how to further narrow your research space. In our household waste example, we could create a baker’s dozen of research papers:

How to reduce household waste for the most commonly purchased household goods

How to reduce household waste for goods that contribute most to landfill

How to reduce household waste for goods that have the most toxic waste footprint

How to reduce household waste volume with an improved method of waste compression

How to augment kitchen layout and design to accomodate food waste reduction

etc.

Each of the above refinements can become a PhD. Some of the above could lead to the invention of commercial products to support the waste reduction efforts. Some of the above could lead to more impact than others. All of the above could lead to interesting and valid research. The actual choice you make depends on what criteria is important to you: do you want to create a new product, invent a new method, change user behaviour, raise awareness or make the most impact. If you don’t know which to choose, don’t stress: all of the above will be good options, so just pick one.

Step #3: validate whether your target audience cares about your topic area, and use their why to narrow your core issues

Do the groundwork

You have now refined your core issues into a valid and inetersting research topic (oh, and BTW, you have just overcome the biggest challenge in research, topic selection!). The next step is to do the groundwork — read the papers that exist in your narrow space.

There are generally two kinds of academic papers: papers on a topic and papers that summarise the state of a particular field. The summary papers typically correlate to literature reviews that an aspiring PhD student has pulled together in their Doctoral journey.

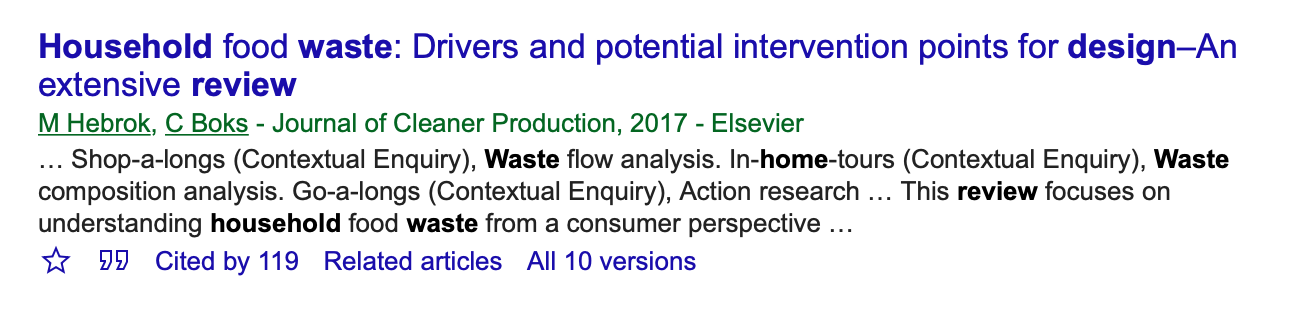

If we take the last of the above household waste topics, How to augment kitchen layout and design to accomodate household waste reduction, I would pick out the main issues (household waste and kitchen design) and add the word review into Google Scholar. Bingo.

Look for papers that review the topic that you are investigating

Recent, well cited papers that provide an extensive review of a field are a really useful place to start deeper research. By reading a paper like this, you will gain a great summary of the research space, a list of references to the most relevant papers in the field, and a framework for how to classify existing works in the field. Unless you are doing a PhD, and even then in most cases, using an established framework is a good way to start to mentally partition the research that exists in your space.

Step #4: print your papers, write a summary sentence on each paper, and arrange your papers into piles that represent your classification framework

Start writing your literature review

You might think that you have nothing to write about, after all, we have not solved any problems, designed or invented anything yet. Writing, and especially academic writing is a marathon — you could go out there and run it without training, but you’ll probably hurt a lot more than if you trained a little. Starting to write at this point is like going for a training run. It won’t be your best work, in fact, it might be seriously s*itty. It does not matter. You should start writing now to get your writing muscles ready.

Academic writing is like a marathon — elements of it are quite formulaic and systematic, just like a training run

Writing a literature review is quite formulaic. Return to your pile of papers, arranged into conceptual groups, each with a summary sentence written accross the top. Take each pile, and write a paragraph about the story that is told by those papers. Add a top and a tail to your paragraphs, and you pretty much have the bulk of your literature review.

In this paper, section 4 is a great example of how a topic like “what impacts food waste” can be broken into conceptual piles, and how each “pile” is constructed to tell the story of that narrower topic, e.g. 4. Food waste drivers → 4.1 Do we realise the true value of food? → 4.1.1 Values and the perceived value of food and 4.1.2 Awareness and attitudes

The structure of your literature review is quite systematic. Follow the process, and you will get there

Step #5: write a paragraph that describes each of your assembled piles of paper, add an intro and summary to create your literature review

*Side note: writing a blog post, or less academic paper

If you are writing a less structured piece, such as a blog post, product release or commercial white paper, take each of your piles of paper and turn them into a separate article. A good rule of thumb is to explore only one idea per piece.

The advantage of following the above process in the preparation phase is that your writing will be backed up by credible sources — even if your original sources are deliberately swapped out for more accessible reads (e.g. a well written article on Medium, or in the Harvard Business Review is much easier for a general audience to consume than an original academic reference). Additionally, starting from more solid research sources helps identify gaps in thinking, allowing you to resolve and ultimately produce a higher quality, more credible piece of writing.

Unlearn everything you know

The next step in the process — and note that we are on step six — is the step that most people start at. It is the fun, creative, solution development phase. It’s so tempting to skip straight to this step, to start sketching out solutions and product designs.

Don’t do this.

If you takeaway nothing else from this article, take away this: the quality of whatever solution you produce will be orders of magnitude higher because you went through the (somewhat formulaic) steps first. This, frankly, is the real value of research, and why some people have the capacity to produce exceptional results, over and over again.

So, onto the fun part. Forget everything. Take out a blank piece of paper, and note how now, rather than being scary, that blank piece of paper is exhillarating. Get lost in sketching out solutions, get lost in dreaming, lose yourself in the flow of creating.

Throw away most of what you create in this phase, and continue sketching. Continue solving, and iterating and going down pathways, and dead ends, and narrow alleways. Give yourself the time that this phase needs — creativity can’t be rushed, and it can’t flourish under conditions of high stress.

The reason why you will notice much higher, more efficient outcomes after completing the first five steps is that those (formulaic, maybe somewhat mundane) steps pre-load knowledge into your subconscious. They arm you with experience in what may be a new field, and give you the ability to apply your problem solving skills to a broader range of problems.

The first five steps are your shortcut to becoming an expert in a narrow domain

Step #6: forget everything, settle into a flow state and sketch out a broad range of solutions. Discard most without attachment, and trust that the process will deliver magic ⭐️

Test your solution

This step can be confronting, as, through no fault of your own, even if you have followed all the previous steps perfectly, you may arrive at a solution that does not work. The great news is that if you have followed the process, once you identify the stumbling points, it won’t take long to retreat a few steps, make adjustments and keep going forwards.

Testing a solution can take many different forms. Technology products can be tested using a variety of usability testing techniques. Design research can be tested using a range of qualitative methods. The method you choose is like a kitchen utensil — don’t be afraid of it, simply pick the best utensil for the job at hand.

And then go and test.

Except that, you don’t want your test to feel like a test. Make your participants feel comfortable, make them feel special, make them understand that there are no right or wrong answers. Don’t justify design decisions, or defend your design choices, don’t even explain your design choices. Ideally, get a buddy to test your design and test theirs in return.

7 Common UX testing mistakes and how to avoid them, Brisbane Wordcamp 2018

Step #7: test your design/solution with a representative target audience

(Build, launch) and finish writing

Depending on the nature of your research and product solution, you might go ahead and build an MVP of your solution, working up to a soft-launch with a small group of participants, refining, fixing and working towards a final launch. Alternately, you may just skip to the final writeup phase.

The terrific news about the final writeup phase is that if you have done the previous steps without shortchanging yourself on the process, this step is largely mechanical. At this stage, you know your space better than anyone else, you understand the drivers, you are the best person in the whole world to write about your research project.

So once again, take a deep breath. Pour yourself a [kombucha | coffee | wine | all] and start the process of telling the story of what you created and why. While most academic writing tends to be hard to understand, I personally prefer to write in a simple, clear way — I actually apply a Mum filter to everything that I write — if my Mum understands what the piece is about, then chances are that others will too (thanks Mum 🙌). Through writing more often, you will develop your own style.

Step #8: write your story. Have confidence that if you followed the research process, your ideas are credible and don’t need to be obfuscated with fancy words

Anna Harrison

Anna Harrison